If heat pumps are to account for a higher-than-2% share of the heat market, we need more rather than less government intervention.

The proposed fund of £100 million represents a two thirds reduction[4] in the support and, quite simply, is insufficient to do the job set out for it. A much larger fund of £1 billion allocated over four years would be better aligned to the consultation’s objectives. This could support up to 250,000 heat pumps, doubling the total numbers.

This would fit better with the CCC’s assessment that we would need £1.5-2.5 billion a year for a rollout of energy efficiency and low-carbon heat through the 2020s. This estimate is for the UK as a whole and does not include the additional funding required for fuel poor households. The carbon saving from a £1 billion scheme would be equal or higher to the biomethane scheme set out in the other part of the consultation, for which up to a £2.8 billion has been proposed.

Clearly, additional funding for anything is difficult right now. But, as Sir John Grieve highlighted, a focussed push of heat pumps would meet his criteria for a productivity-focussed stimulus.

When implemented alongside wider measures, such as reducing the cost differential between heating fuels and regulation or an emissions standard for replacement heating in off-grid homes, this scale of fund could transform the sector.

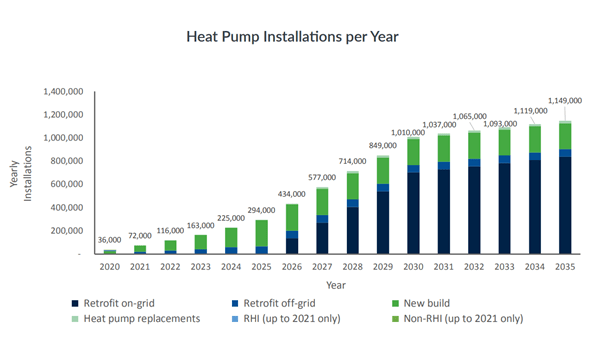

[1] CCC Fifth Carbon Budget, Central Scenario

[2] UK Government ‘The Future Homes Standard‘ (October 2019)

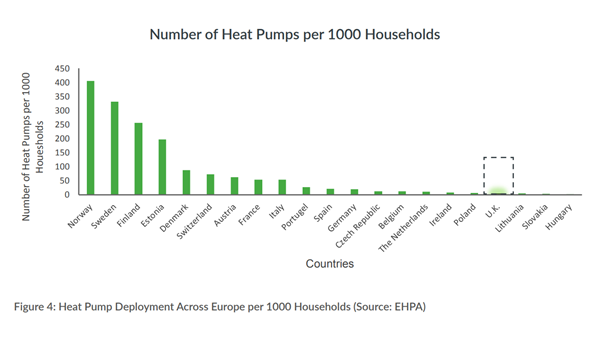

[3] Nowak et al. (2014) from M.J Hannon (2015)

[4] Based on the RHI forecasted spend for 2020/21