A gas revolution is brewing in the north – and this time, there’s no fracking required.

Northern Gas Networks (NGN) is looking to turn Leeds into a world-first ‘hydrogen city’ by 2030 at the latest, while setting the tone for a UK-wide replacement of methane by hydrogen on the gas grid. It’s certainly a bold vision.

A H2 option, made in Yorkshire

Dan Sadler, who manages the H21 project, explained the logic at a recent seminar on creating a hydrogen gas network.

He said: “Meeting the targets of the climate change act is a big challenge, big challenges need big ideas. Conversion of the UK gas grid from natural gas to hydrogen could present the biggest single contribution to meeting that challenge.”

With 80% cuts in greenhouse gas emissions on 1990 levels required by 2050, and 80% of UK homes using natural gas for heating, an alternative that produces only water when burnt, as opposed to carbon dioxide, looks very attractive indeed.

Image via Northern Gas Networks (L-R: Mark Lewis, Mark Crowtherm, Dan Sadler, Alastair Renee and Melanie Taylor at launch of H21 Leeds City Gate report in London)

Re-jigging the grid

Hydrogen is the most abundant chemical element on the planet, but its pure form can only be achieved via electrolysis or chemical processes.

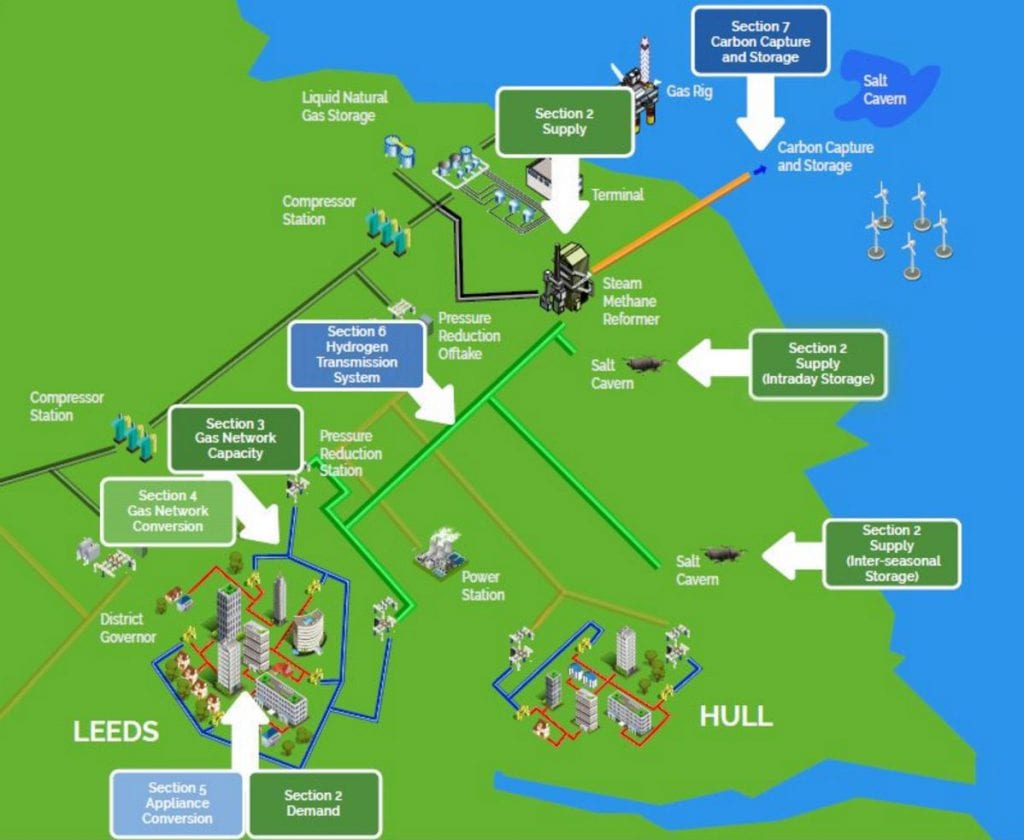

The process that forms the heart of the Leeds plan requires ‘steam methane reformer’ plants, taking methane from the grid and turning it into hydrogen for use in the city. This removes carbon, which will then be captured and stored.

In terms of the infrastructure needed to make it happen, it involves using existing underground pipes, and householders wouldn’t have to change their appliances – though they would need to be converted en masse to work using the new fuel.

This wouldn’t be unprecedented, with the UK having previously taken on an undertaking of similar scale and design. Sadler explained:

“We’ve done this before, when we converted the UK from towns gas (containing 50% hydrogen by volume) to natural gas between 1966 and 1977. Converting the natural gas grid to hydrogen is technically possible and it would allow us to make use of the existing assets whilst having a minimal impact on customers versus any alternative decarbonisation option.”

The start of something big?

The plans have already received funding from energy regulator Ofgem, with the possibility of further money to delve more deeply into the safety aspects of a hydrogen network. It’s possible that there may be a formal government policy decision about moving over to hydrogen in the early part of the next decade.

Efforts in the search for low-carbon changes that can be instigated with minimum disruption and costs for the average consumer can only be welcomed. In particular, new approaches to tackle the significant sustainability issues connected with heating homes and businesses are particularly needed.

With significant local opposition to fracking for gas, and only one such project started so far, hydrogen may well provide a practical option to maintain home comforts and make significant emissions cuts.

Of course, to become a reality rather than a nice idea, this will require significant and sustained investment – but there’s no doubt that this is a concept worthy of some serious exploration.

Further reading

Is renewable heat right for your home?

In order to reach net zero targets we’re going to need to dramatically reduce the amount of fossil-fuel generated heating in our…

NewsA promising start for a green recovery

We welcome this morning’s announcement for a £3 billion green stimulus investment with a focus on improving energy efficiency and heating.

BlogGreen and corporate giants agree: a clean energy transition is needed now

Only a few years ago, it would have seemed absurd to suggest that Al Gore and Royal Dutch Shell might come out…